Unbelievably committed

It was the moment that made Vanessa Nakate question everything: the value of her work, her own self-image, and deeper yet, the meaning of it all. A year and half has passed, but even now the 24-year-old climate activist from Uganda still seems troubled when she talks about it in a video call. “I was shaken up”, she says, “It hurt.”

Nakate is the face of Fridays for Future on the African continent. So strong is her association with the movement, she is often referred to as “the African Greta”. In January 2020 she travelled almost 6,000 kilometres from her home country to Davos, Switzerland to promote climate protection at the World Economic Forum. After a press conference, she posed for a group photo with four fellow campaigners before a backdrop of snowy, sunlit mountains.

However, when the photo was featured in the press later, Greta Thunberg, Luisa Neubauer and two other European activists (all white) were present. Only Vanessa Nakate was missing. A photo editor for the Associated Press news agency had cropped her out of the photo. “Only part of my jacket was still there”, Nakate recalls. She, a black climate activist, had simply been “erased”.

Activists like Nakate are taking to the streets, trying to put pressure on international politics, and at the same time, aiming to expand their networks to Europe. They’re also starting their own projects to mitigate the consequences of climate change locally. Accompanying these activists over the coming year, The Tagesspiegel will be offered an insight into a grassroots movement that is pursuing the same goals a Thunberg, Neubauer and co.: a climate-neutral world. Fatou Jeng from Gambia, Hindou Oumaru Ibrahim from Chad, Ineza Umuhoza Grace from Rwanda and Vanessa Nakate from Uganda will kick off the series.

Although they have the same goals as European activists, their methods are different. Instead of calling for school strikes, they plant trees, collect garbage, and organise educational campaigns - often under difficult conditions. Their struggle is one for survival, but also one against old prejudices, from traditional ideas about “the proper role of women”, to the cliché of Africa as a continent of perpetual crisis.

Fatou Jeng When home is swallowed by the sea

Describing herself as a “climate optimist”, the 24-year-old Fatou Jeng from Gambia says: “We are a generation that is changing the narrative about Africa.” Speaking to the Tagesspiegel via video from student accommodation in Sussex, UK, Jeng explains that right after the call, she has a seminar at university. Aiming to finish her Master’s in Development Studies by September, she plans to return to Banjul, Gambia’s capital, where she was born.

Her struggle is one against time. When she talks about her home, she talks quickly and anxiously. Banjul is in acute danger. With a population of 30,000, it’s built on the mouth of the Gambia River, where its dark waters flow into the Atlantic. “The town is going to sink”, Jeng says. “It will not only cost lives, but also destroy our cultural heritage.”

Whenever floods and heavy rains submerge the streets, many people die. By 2050, when Jeng will be in her mid-50s, large parts of Banjul are expected to be swallowed by the sea. By then, the historic centre with its old colonial buildings will be just a tiny island in the Atlantic.

The government can do little about it; Gambia is not only small - about half the size of Hesse - it’s also poor. Politicians lack both the means, and the political will to take action against littering or illegal loggers, says Jeng. There’s been one small success however: the environment minister supports her project, “Clean Earth Gambia”.

Her organisation, founded in 2017, has planted 5,000 coconut trees around Banjul so far -knee-high seedlings that can grow to be as taller than houses, all completely financed by donations. Their roots should prevent the coast from complete erosion. 3,000 more trees are to follow. Jeng believes in action, not protest: “I think it’s more effective than school strikes”, she says. Education is a privilege in the country where half are illiterate. Few people would have sympathy for schoolgirls on strike.

Jeng’s father, a smallholder farmer, was initially put off by her activism, she comments. “People expect girls to stay at home and take care of the household”. But now the whole family is proud of her commitment.

Hindou Oumaru Ibrahim Learning from indigenous communities

Travelling around the world for her mission, Hindou Oumaru Ibrahim from Chad approaches the climate issue in a very different way from her fellow campaigner in The Gambia. Her relatives are also proud: “they stand somewhere in the desert, show my videos on their smartphones and say: ‘my cousin is ‘high-level’”, says Ibrahim. ‘High level’ meaning a participant in high-level international conferences and UN meetings. In April, she even gave a speech at US President Joe Biden’s climate summit.

“It is time for you to listen to us!” she urged. Her message: the world needs help to stop climate change, particularly the help of indigenous communities. This is because they know how to best protect ecosystems. Ibrahim is fighting for these communities to have a seat at the negotiating table of big politics.

That the daughter of a cattle rancher would become a climate campaigner in demand around the world was not - exactly - expected. Her mother sent her to school despite encountering resistance from her other family members, who wanted to marry her off early. Then, Ibrahim says, she was discriminated against in class because of her heritage. “When you’re born indigenous, you’re born an activist”, she says. “You fight every day for your land, your way of life, against the destruction of the environment.”

Anyone meeting her for the first time realises she is a consummate professional. They’d be immediately emailed by her assistant from the US, with fact sheets and personal information about her boss - about her work and about Ibrahim’s childhood in the south of the Sahara.

Where the savannah gradually becomes rainforest, the Mbororo live with their cattle herds. The nomads breed cattle, stately animals with horns as wide as a small car. “The meat and milk are carbon neutral”, she says. The nomadic lifestyle preserves the land, she says, and the cow dung makes it fertile. In their search for fresh pastures, the Mbororo orient themselves using the wind, the clouds, or swarms of insects.

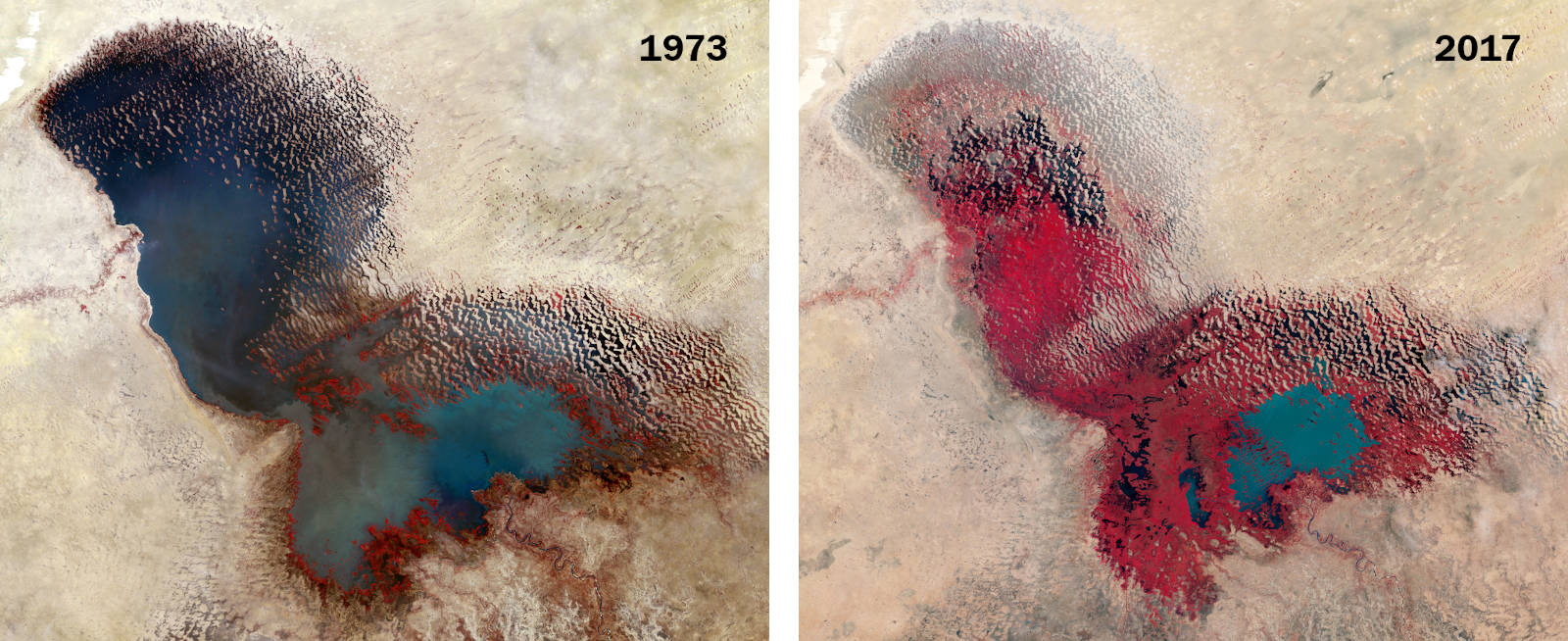

But their environment is changing. Global warming is progressing one and a half times faster in the Sahel than in the rest of the world. “In my country, we are long past the 1.5 degree target”, says Ibrahim. The consequences are tragic: children and the elderly are dying from the increasingly frequent heat waves, and cows are giving only a quarter of the milk they did 20 years ago. Lake Chad, the region’s life source, is drying up.

Cattle herders and farmers fight over the lake, often with weapons. Many men go to the city to look for work. Others receive offers from Boko Haram, an Islamist terrorist group: a machine gun and $500. “Someone who otherwise earns $50 a year will easily accept something like that”, Ibrahim says. It’s not just the money, she explains, it’s about regaining dignity as breadwinners.

Ibrahim’s fight against the climate crisis is therefore also one against violence. She has developed a 3D programme for mapping Chad in order to harness the ancient knowledge of indigenous women using modern methods.

Ineza Umuhoza Grace Progress, but sustainable

It is not so easy to get Rwanda’s populace excited about climate protection but Ineza Umuhoza Grace is trying anyway, by founding the organisation “The Green Fighter”. The fact that the graduate civil engineer preferred to earn “green money” rather than take up a ‘normal’ profession did not go down well with her family at first, she says. This didn’t come as a surprise: her family were merely reflecting the attitude of the general public about the need to make money.

The country wants to look forward, past the genocide of 1994. The economy has grown by around 10% in each of the past few years. Those who can participate in the rapid growth, want to wholeheartedly, and leave poverty behind. Climate issues are not high on the list of concerns for many citizens.

Grace wants to change that. From the small office of a solar company in the capital Kigali, she organises climate campaigns for primary schools. 3,500 pupils have taken part so far. Climate protection is not dealt with in schools, she says. She and her team address this by making young people ready for the problems of the future.

Rwanda is nicknamed “the land of a thousand hills”. The rainy season is becoming both shorter and also more intense. Cloudbursts cause mountain landslides. They sweep away the maize and millet fields, and often, even entire villages. “My family had a small, cosy house with a kitchen and four rooms”, Grace says. One night, after days of heavy rain, a mudslide thundered through their village in northern Musanze District, burying the houses. The family was lucky: they survived. Other villagers died in their sleep. Roughly 1,000 families were left homeless.

“These stories happen far too often”, Grace says. The money to rebuild destroyed houses and roads is lacking: in many places, there’s not enough money for schools and hospitals. Climate change threatens the country’s development. “Progress is being washed away”, Grace says. But she doesn’t just want her countrymen to understand her concern. It’s important that internationally, she says, Africa’s climate movement gets more attention: “We are speaking, but we are not being heard.”

Vanessa Nakate Women on the front lines of the climate crisis

Being active locally and lobbying globally at the same time: the motif that runs through many female climate activists’ work. Nakate, for one, used the unplanned attention she received after being cut from the photo in Davos to further her cause. “For me, it was a turning point”, she says.

At the time, she wrote, “You didn’t just delete a photo, you deleted an entire continent.” The incident showed the whole world: of all people, those who are least responsible for climate change, but hardest hit, were being ignored in the public debate. After all, only 3% of global CO2 emissions are attributable to African countries. For the people in the Global South, however, the consequences of climate change are already very tangible, and in some cases life-threatening.

African women and girls in particular bear the brunt of climate change. The more the environment changes, the bleaker their future looks. “Women are on the front lines of the climate crisis every day”, says Nakate. They are the ones who walk the distance to the nearest water point when there is a drought. Or who have to get food for the family when the crops have been destroyed by storms. A life in peace, their chances of education, the health of their children: climate change takes all that away from them.

Vanessa Nakate wants to do two things, therefore: shake up the economic elites in Davos and create more awareness in her home country about how much climate change is affecting all areas of life. From the farmers’ harvests, to the fishermen on the shores of Lake Victoria, whose huts are being washed away.

Nakate grew up just a few kilometres from Lake Victoria, in a suburb of Uganda’s capital Kampala. For more than two years she has been on strike for the climate. Of course, you have to be able to afford that in a country where 20% of the population live below the poverty line. She was lucky that her parents managed to move up into the growing middle class, giving her the freedom to get involved.

It wasn’t until after she finished her business studies that she began to look more closely at the consequences of climate change. Nakate volunteered at the Rotary Club, where her father was also involved. During her research, she came across a topic that she had only previously known from geography classes in an abstract form. “I didn’t realise until that moment that climate change is one of the biggest threats to people’s lives”, she says.

She read about Fridays for Future and decided to join the movement. Since then, every Friday she stands with a sign in her hand at busy intersections, gas stations, or in front of the parliament. Sometimes alone, sometimes with a small group.

She says she regularly experiences insulting comments and disapproving looks. But Nakate also recounts situations in which people threatened to have her arrested. Once, a scuffle broke out in front of the well-guarded parliament building. Police officers looked suspiciously at her placard, searching for hidden criticism between the lines, asking themselves if she was from the opposition. “I am concerned about our common environment”, she told them. In Uganda, opposition activists often end up in prison, and hundreds have disappeared in recent months alone. Some end up in court, others are found dead, and there is simply no trace of many others. Just this January, Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni was confirmed in office, a position he has held since 1986. His challenger complained of massive problems during the election campaign, including arrests and torture. Unlike one of her fellow campaigners, she herself has not yet been arrested, says Nakate. She tells of an acquaintance whose employer threatened to fire her if she continued to protest against the construction of the oil pipeline from Uganda to the Tanzanian coast. This was because a protest against the pipeline was in opposition to her own government.

When Fridays for Future called for a global strike day in March this year, Nakate did not try to organise a school strike. For fear of getting into trouble with parents or teachers, many students did not dare to leave class. On this day, she went to one of the schools for which she has collected donations to equip them with solar panels and environmentally friendly stoves. Her aim: to show young people ways forward in the problems they are up against.